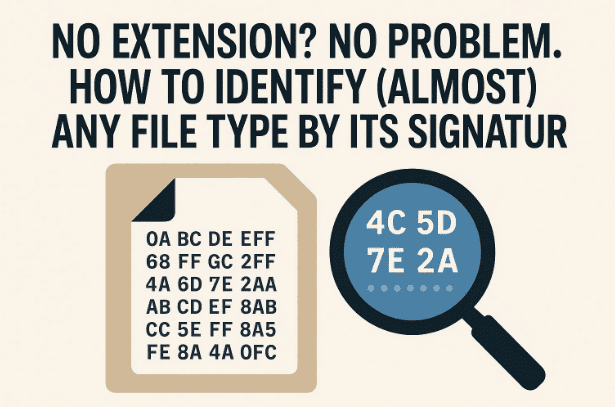

We’ve all been there: you download a file, it has no extension, and nothing opens it. You try a few guesses—.mp4, .mkv, .pdf, .zip—and your apps shrug. Frustrating, right? The good news is that most files carry their identity inside them. With a few careful steps, you can often figure out the real type of a file—even if the extension is missing or wrong.

In this detailed guide, we’ll walk through how file signatures (a.k.a. “magic numbers”) work, how to inspect them safely, and how to interpret what you see. We’ll also cover container formats (like AVI/MP4/Matroska), why a “video file” isn’t just one thing, and what to do when signatures are ambiguous. Along the way, I’ll add practical tools and workflows for Windows, macOS, and Linux, plus a short Q&A to clear common doubts.

Before we dive into step-by-step instructions, one tiny correction to the original script: the word “hexadecibel” pops up. The correct term is hexadecimal—base-16 notation commonly used to display bytes. No worries if that sounded exotic; you’ll be reading hex comfortably in a moment.

What’s a File Signature (Magic Number), Really?

Let’s move to the heart of the matter. So far, we’ve done a good job setting the stage—now let’s talk about why files can be recognized without extensions.

Many file formats begin with a short, fixed sequence of bytes at the very start of the file. This “hello, I’m X!” is called the file signature or magic number. Operating systems and tools use these bytes to identify the file’s container type—even if the file extension is wrong or missing.

- A classic example is Windows executables. The first two bytes are

4D 5Ain hex, which are the ASCII lettersMZ. Those initials belong to Mark Zbikowski, the Microsoft engineer who defined the format. If a file starts withMZ, it’s almost certainly an EXE (or DLL, a close relative). - PDF files begin with ASCII text:

%PDF-1.x(you can literally see it if you open the file as text). - ZIP archives usually begin with

50 4B 03 04(which isPK..in ASCII).

You get the idea: the first few bytes are often enough to recognize the container.

Important: A signature tells you what container you’re dealing with (e.g., “this is a ZIP” or “this is a PDF”). It doesn’t always tell you what’s inside (e.g., which audio/video codec is inside an MP4, or which files are inside a ZIP). We’ll cover containers and codecs shortly.

Why Extensions Fail (and Signatures Shine)

Extensions are a convenience; they’re not truth. They can be missing, deliberately changed, or mangled during download. Signatures don’t care: they sit at byte zero of the file and say, “I am what I am.”

That’s why our approach is to ignore the extension and inspect the bytes—then match what we see to a known signature.

The Safest Way to Investigate an Unknown File

Let’s pause for a practical, safety-first moment. We’re about to use powerful tools that can also modify files. So here’s a cautious routine you can follow every time.

- Make a copy of the unknown file.

Work only on the copy. If you accidentally change something, your original remains intact. - Scan the file before poking it.

Upload it to VirusTotal (free) to see if multiple engines flag it. This doesn’t guarantee safety, but it’s a smart first gate. - Never run an unknown file.

Our goal is to identify, not execute. We’ll be reading bytes, not launching anything. - Prefer read-only tools or “view” modes.

If your hex editor can lock files read-only, use that. If not, just don’t type or save changes. - If you must open it later, open it with a trusted viewer (e.g., a media player or a PDF reader), and only after you’re reasonably sure of the type.

Alright—tools at the ready? Let’s inspect.

Tools You Can Use (Windows, macOS, Linux)

We’ve been talking about looking at “the first few bytes.” How do we actually do that? You have multiple options—from GUI hex editors to command-line utilities that identify file types for you.

Windows (GUI & CLI)

- HxD (free hex editor): https://mh-nexus.de/en/hxd/

Excellent for viewing bytes. It also highlights changes in red if you edit (don’t!). - CertUtil (built-in):

certutil -hashfile <path> SHA256(for checksums; doesn’t show headers, but useful for integrity). - Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL): Gives you Linux tools like

fileandxxdon Windows.

macOS

- Hex Fiend (free hex editor): https://ridiculousfish.com/hexfiend/

- file (built-in):

file <path>uses magic databases to identify types. - xxd (built-in):

xxd -l 32 <file>shows the first 32 bytes in hex.

Linux

- file (built-in on most distros):

file <path> - xxd (often included with Vim):

xxd -l 32 <file> - Bless (GNOME hex editor) / wxHexEditor (cross-platform GUI) if you want a visual editor.

For media/container details

- MediaInfo (Windows/macOS/Linux): https://mediaarea.net/en/MediaInfo

Tells you container, codecs, bit rates—perfect when a file is “a video” but won’t play. - ExifTool (Windows/macOS/Linux): https://exiftool.org/

Great for metadata on images, PDFs, and more. It won’t always solve video codecs, but it’s invaluable elsewhere.

You don’t need all of these. If you’re on Windows, HxD + MediaInfo will cover most cases. On macOS/Linux,

file+xxd+ MediaInfo is an excellent combo.

Step-by-Step: Identify a File by Its Signature

We’ve set the stage well—now let’s move to the main event and go through a repeatable, low-stress process.

Step 1: Open the file in a hex viewer (safely)

- Windows (HxD): Launch HxD → File → Open → select your copy of the file.

You’ll see the left column (offsets), the middle column (hex bytes), and the right column (ASCII view). - macOS/Linux (xxd):

xxd -l 32 unknown.binThis prints the first 32 bytes—usually enough to spot a signature.

Step 2: Read the first few bytes

Look at bytes 0–8 (and sometimes further). Some signatures are ASCII and easy to spot; others are non-printable hex.

Examples you’ll commonly meet:

- EXE/DLL (Windows PE):

4D 5A→ “MZ” - PDF:

%PDF-→25 50 44 46 2D - PNG:

89 50 4E 47 0D 0A 1A 0A - JPEG:

FF D8 FF(often followed byE0orE1) - GIF:

47 49 46 38 39 61(“GIF89a”) or47 49 46 38 37 61(“GIF87a”) - ZIP:

50 4B 03 04(PK..), sometimes50 4B 05 06(empty archive) or50 4B 07 08 - RAR:

52 61 72 21 1A 07 00 - 7-Zip:

37 7A BC AF 27 1C - GZ:

1F 8B - BZ2:

42 5A 68(“BZh”) - ELF (Linux executable):

7F 45 4C 46 - MP3 (w/ ID3):

49 44 33(“ID3”) - OGG:

4F 67 67 53(“OggS”) - RIFF (container for WAV/AVI):

52 49 46 46→ “RIFF” at byte 0, withWAVEorAVIat byte 8 - RIFF (WebP):

52 49 46 46at 0, withWEBPat byte 8 - MP4/QuickTime family: often

66 74 79 70(“ftyp”) around byte 4; the brand (e.g.,isom,mp42,qt) follows - Matroska (MKV/WebM): starts with EBML header

1A 45 DF A3

Pro tip: If you see

PKat the start of a file that you thought was a DOCX, XLSX, or PPTX, that’s correct—modern Office files are actually ZIP containers. Rename to.docx(or the right Office extension) and your editor should open it.

Step 3: Match what you see to known signatures

- If you’re using Linux/macOS, try:

file unknown.binThefileutility uses a database of signatures and often returns a clear answer (e.g., “PNG image data” or “ISO Media, MP4 Base Media v1 [IS0 14496-12:2003]”). - If you’re on Windows, glance at the ASCII pane in HxD.

%PDF-andRIFFare plainly readable. For non-printable magic numbers (e.g.,89 50 4E 47), keep a small table handy or search “PNG signature” in a trusted reference.

When multiple formats share similar headers, compare the longest matching sequence, not just the first two bytes. And always consider context: where did the file come from? What did you expect it to be?

Step 4: Adjust the extension (carefully)

Once you’re confident:

- Rename the file with the correct extension (e.g.,

.png,.pdf,.zip,.mp4,.mkv). - Open in a viewer appropriate for that type. Don’t run executables you didn’t expect (e.g., something that turned out to be

EXE).

Step 5: If it’s a container (video/audio/archive), inspect inside

Identifying “this is MP4” doesn’t guarantee it will play. MP4, AVI, MKV, OGG, and others are containers that can hold streams encoded with many different codecs. Your player needs the right codec support.

- Use MediaInfo to see container + codecs:

https://mediaarea.net/en/MediaInfo

You’ll learn if the video is H.264, H.265/HEVC, AV1, VP9, etc., and which audio codec it carries (AAC, Opus, AC-3…). Then you can choose a player that supports them (e.g., VLC, MPV) or install the necessary codec support on your OS.

Real Examples (So You Know What “Success” Feels Like)

Let’s string this together with a few tiny wins. You’ll start recognizing these quickly.

- Unknown file shows

25 50 44 46 2Dat the start.

That’s%PDF-. Rename to.pdf. Open in your PDF viewer. Done. - Unknown file starts

52 49 46 46and at byte 8 you spotWAVE.

That’s a WAV audio file. Rename to.wav. - Unknown file starts

50 4B 03 04.

That’s ZIP (also the base for.docx,.xlsx,.pptx). Try renaming to.zipand see if it opens, or if you know it’s a Word document,.docx. - Unknown video is recognized as MP4 (ftyp…isom), but won’t play in your default app.

Open in MediaInfo and check codecs. If it’s HEVC (H.265) and your system lacks the decoder, try VLC or MPV (both include software decoders), or install the needed codec. - File starts with

MZand you expected a picture.

That’s a Windows EXE/DLL. Do not run it. It’s not an image; it’s executable code. Delete if untrusted.

Beyond Signatures: Other Clues That Help

Sometimes signatures are ambiguous or missing (corrupt files, partial downloads, or very obscure formats). In those cases, combine signature checks with:

- File size and structure

Does the size make sense (e.g., a “video” that’s only 12 KB is suspect)? Are there readable strings beyond the header (xxdorstrings <file>on Unix can help)? - Metadata tools

ExifTool (https://exiftool.org/) often reveals image/document metadata even when extensions are wrong. - Reputable references

Although there’s no single exhaustive list, community-maintained collections (e.g., “file signatures” pages) can be helpful. Cross-check with multiple sources. - Source context

If the file came from an email, cloud sync, or a known application, that narrows likely types.

What If I Still Can’t Identify the File?

Let’s not give up yet. You’ve done a solid job so far—time to try a couple of extras.

- Try

fileon Unix/macOS (or via WSL on Windows).file -k unknown.binThe-kflag will keep going and print additional details. - Try a different hex viewer to ensure what you’re seeing isn’t an artefact (rare, but worth a shot).

- Check if the file is truncated (compare size with what you expected; look for partial headers).

- Consider encryption or compression

Fully random-looking headers and no readable strings may indicate encrypted data or a proprietary container. - Last resort: ask with samples (safely)

On trusted forums (redact sensitive data), you can share the first 64–256 bytes (header only). Experts may recognize a format by sight. Never share private content without sanitizing it.

Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

Just before we jump into some quick reference tables and Q&A, here are mistakes worth sidestepping.

- Editing the file in a hex editor and saving

Don’t. Always work on a copy—and in read-only mode if possible. - Assuming the first match you see is correct

Some bytes are shared across families. Match the longest signature you can. - For video: thinking container = codec

Remember: MP4/MKV/AVI are boxes, codecs are what’s inside. Use MediaInfo to know which decoders you need. - Opening unknown executables

If the signature says MZ (EXE/DLL) or ELF, do not run it—especially if you expected a photo or PDF. - Skipping malware checks

A quick upload to VirusTotal is a low-effort, high-yield safety step before any deeper analysis.

Quick Reference: Signatures You’ll See All the Time

To make your next identification even faster, here’s a compact list you can paste into a note. Let’s move to this handy cheat sheet; you’ll probably memorize a few after a week of use.

- EXE/DLL (PE):

4D 5A(“MZ”) - ELF:

7F 45 4C 46 - PDF:

%PDF-→25 50 44 46 2D - PNG:

89 50 4E 47 0D 0A 1A 0A - JPEG:

FF D8 FF - GIF87a:

47 49 46 38 37 61 - GIF89a:

47 49 46 38 39 61 - ZIP (incl. DOCX/XLSX/PPTX):

50 4B 03 04(or50 4B 05 06,50 4B 07 08) - 7-Zip:

37 7A BC AF 27 1C - RAR:

52 61 72 21 1A 07 00 - GZ:

1F 8B - BZ2:

42 5A 68 - RIFF (WAV/AVI/WEBP):

52 49 46 46at byte 0 → look at byte 8 (WAVE,AVI,WEBP) - MP3 (ID3):

49 44 33 - OGG:

4F 67 67 53 - MKV/WebM (EBML):

1A 45 DF A3 - MP4/QuickTime family: look for

ftypnear byte 4 (e.g.,isom,mp42,qt)

Q&A: Quick Answers to Common Questions

Q: I renamed the file to the “right” extension, and it still won’t open. Why?

A: Either the file is corrupt, or you’ve identified the container but lack the codec or proper app. Use MediaInfo to check which video/audio codecs are inside an MP4/MKV/AVI, then try a player like VLC or MPV.

Q: The header looks random—no ASCII, nothing recognizable. What now?

A: It could be encrypted or compressed in a proprietary way. Try the file command; if it says “data” (no identification), you may need context from the source or a specialized tool.

Q: Wikipedia shows multiple formats for the same first bytes. How do I choose?

A: Match the longest sequence that fits your file, not just the first two bytes. Then cross-check with context (where it came from, expected content).

Q: Is there a one-click tool that “just tells me”?

A: On macOS/Linux, file <path> is often remarkably accurate. On Windows, you can install WSL to use file, or rely on MediaInfo for media files and HxD + a signature table for everything else.

Q: Can I rescue a file if the header is damaged?

A: Sometimes, yes—if you know exactly what’s missing and you have a template from a valid file of the same type. But this is an advanced, risky maneuver. Work on a copy and consider expert help for important data.

Q: I expected a document, but the file starts with MZ.

A: That’s a Windows executable (EXE/DLL). Don’t run it. It’s either the wrong file or someone’s trying to trick you.

A Practical Workflow You Can Reuse

Let’s bring everything together with a short, repeatable checklist. So far we’ve covered a lot of ground; this is your ready-to-go routine.

- Duplicate the file and scan on VirusTotal.

- Peek at the header (HxD, Hex Fiend, or

xxd -l 32). - Match the signature to a known format (use

fileif available). - Rename with the correct extension and try a safe viewer.

- If container: run MediaInfo to learn codecs; pick the right player.

- If ambiguous: match the longest header, consider context, try metadata tools (ExifTool), or ask for help with sanitized header bytes.

- If executable when you expected a doc or image: stop and delete unless you truly trust the source.

A Note on Historical and Obscure Formats

You might occasionally run into signatures from older systems (e.g., classic Windows WinHelp files have leading bytes 3F 5F, the ASCII for ?_—a playful nod to the Help icon). These cases are a reminder that:

- Not every signature list is complete or canonical.

- There may be multiple interpretations for a short byte sequence.

- Your best allies are context, longer matches, and sane assumptions.

When in doubt, don’t force a file open just to satisfy curiosity—especially if it came from untrusted sources.

Closing Thoughts (and a Confidence Boost)

You don’t have to be a developer to read file signatures. With a tiny toolset and a steady approach, you can identify most orphaned files in minutes. Extensions can lie; headers rarely do. And when a file is a container, tools like MediaInfo turn “mystery video” into a concrete answer about which codecs you need.

We’ve done a thorough job: you now know what magic numbers are, how to view them, how to interpret them, and what to do when they’re not enough. Keep this guide and the quick reference table handy. The next time a file won’t open, you’ll know exactly where to look—and what to do next.

Software & Utilities Mentioned (Official Links)

- HxD (Windows) – Hex editor/viewer: https://mh-nexus.de/en/hxd/

- Hex Fiend (macOS) – Hex viewer/editor: https://ridiculousfish.com/hexfiend/

- MediaInfo (Win/macOS/Linux) – Container & codec inspector: https://mediaarea.net/en/MediaInfo

- ExifTool (Win/macOS/Linux) – Metadata swiss-army knife: https://exiftool.org/

- VirusTotal (Web) – Multi-engine scanner: https://www.virustotal.com

(Command-line utilities like file and xxd are built into macOS/Linux and available on Windows via WSL.)

Disclaimer

Hex editors and low-level tools can modify files and, if misused, harm system stability or data integrity. Always work on copies, avoid saving changes unless you absolutely know what you’re doing, and never run an unknown executable. This article is for educational purposes; use your judgment and follow your organization’s security policies when handling unknown files.

Tags

file signatures, magic numbers, identify file type, missing extension, hex editor, HxD, Hex Fiend, MediaInfo, ExifTool, container vs codec, mp4 mkv avi, pdf png zip rar, virus total, linux file command

Hashtags

#FileForensics #HexEditor #MagicNumbers #MediaInfo #PDF #PNG #MP4 #MKV #ZIP #CyberSecurity